Fill out the form below to download the full report.

How big a part has a valuation gap played in stalling North American mid-market M&A? Virtual data room provider Firmex worked with Mergermarket to ask six leading experts for their take. See the results below in this edition of our quarterly report on North American mid-market M&A.

Foreword

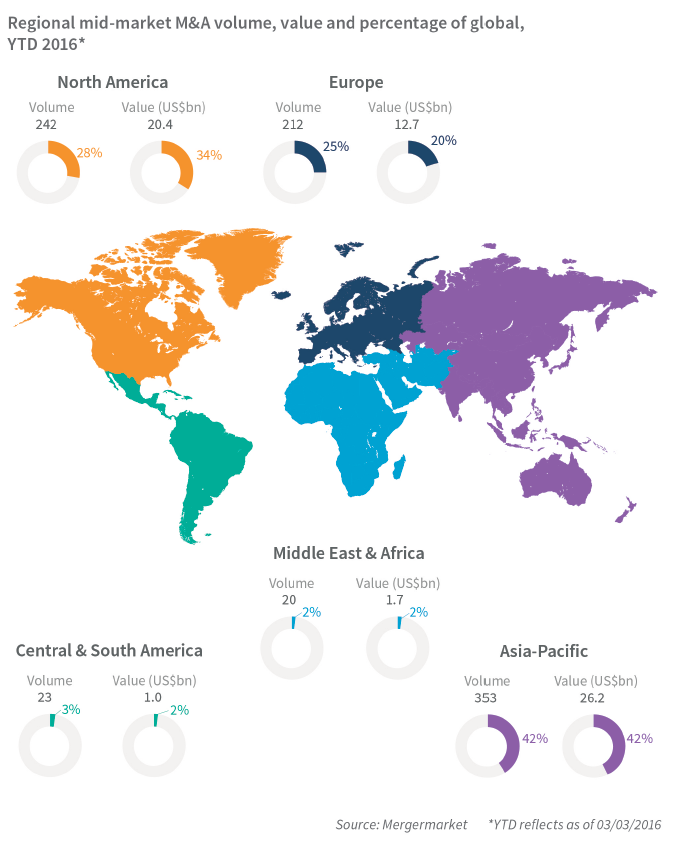

Over the last year, a paradox has persisted in the North American mid-market: buyside interest in deals has been at an all-time high, and yet the number of deals has fallen. In fact, it was the worst January in 25 years for mid-market deals in 2016. What’s going on?

Part of the explanation is a valuation gap between buyers and sellers. High-quality targets in the mid-market have become few and far between, and sellers are trying to leverage that scarcity to peg their valuations a notch higher. Buyers do not always get on board, particularly in frothy sectors such as technology and life sciences, creating a divide. However, the picture could change in the coming year. According to our expert panelists, a macroeconomic downturn may temper expectations on the part of sellers, allowing the two sides to find consensus on valuations. Technical solutions such as earnouts can also be part of the solution.

With corporate cash holdings and private equity dry powder still at high levels, the appetite for mid-market deals will remain robust. The question is: How can buyers and sellers close the valuation gap?

Mergermarket (MM): According to Mergermarket data, the number of mid-market deals (US $10m-$250m in value) fell considerably in North America in 2015. Observers point to a growing valuation gap between sellers and buyers as part of the reason for the fall in deal volume. In your opinion, what factors have been widening the valuation gap in mid-market deal negotiations?

Joseph Feldman (JF): From my perspective, the responsibility for the valuation gap is probably more on the sellers’ side than on the buyers’ side. In my discussions with business owners over the last year, fairly often I’ve encountered what I would say are unrealistic expectations about valuation multiples. Owners sometimes see reports in the press or hear stories from their peers about deals getting done at multiples that they consider to be representative of the entire market, when that just may not be appropriate. On the buyside, I think there’s a tremendous amount of pressure and competition among private equity firms looking for attractive deals. That competition puts pressure on them to pay more over time.

Many of the middle-market companies I consult for are regularly looking for add-on opportunities, and they’ve been relatively steady in looking at core business valuation and synergy opportunities. But they’re not fundamentally changing the multiples that they’re prepared to pay.

Andrew Lucano (AL): I definitely agree that there is a valuation gap going on. The biggest factor is that sellers’ expectations have been raised very high, as Joe mentioned, because they’re looking at the multiples in these mega-merger deals and then trying to apply those same multiples to their middle-market companies. But it doesn’t really always translate. The other thing in the middle market is that there is a dearth of solid businesses with strong earnings that are being sold. So there is extreme competition to get those businesses, which raises the prices for them, even if their financials don’t support such high valuations.

Andrew Hulsh (AH): The current valuation gap that we’re seeing lately has resulted primary from the substantial competition among private equity sponsors and strategic buyers for high-quality investments and companies and the availability of relatively inexpensive financing, which has resulted in extraordinarily high valuations for companies and assets that are for sale on the market. The valuations for many companies relative to their earnings, or EBITDA, are at unprecedented levels. I’m also seeing a decrease in deal volume from private equity sponsors which I believe is the direct result of this “frothy” deal market. Private equity buyers, as distinguished from strategic acquirers, are simply unwilling to pay these extraordinarily high valuations in many cases, unless the companies they’re considering are virtually unblemished. PE firms, unlike strategic buyers, have specific targeted rates of return from their investments, and often these high valuations that we’re seeing have caused these PE sponsors to be more hesitant to proceed. Simply put, where the valuations for particular investments and assets are priced at the top of the market, it becomes more challenging for PE sponsors to obtain their required returns for their investors.

On the other hand, operating companies have strategic needs and growth objectives that, in certain cases, can be more easily met by acquiring companies rather than through organic growth. And these strategic corporate buyers, unlike private equity sponsors, may not need to be quite as concerned about the short-term impact of paying a higher price for these companies and assets, and can sometimes offset the premiums paid for these companies in part through business synergies and related cost savings. So we are seeing an even greater proportion of companies that would normally be acquired by private equity firms being acquired by strategic corporate buyers.

David Althoff (DA): As described above, there were a lot of deals in late 2014 and early 2015 that were completed at really strong multiples, and potential sellers increased their expectations based on these valuations. These marquee deals drove the tone in many industries – building products, industrial distribution, consumer products, and restaurants. It is important to keep in mind, these deals were often aggressively leveraged and the multiples paid were arguably too high. So part of the gap is simply prevailing expectations.

Part of the gap is also caused by unrealistic comparisons that companies make. We were involved in a deal for a building products distribution company at 10x EBITDA – but the management team was fantastic, their systems were unbelievable, and you could really leverage its infrastructure and put tuck-in companies on top. If you compared it with other firms in the same sector, there was a reason they got a premium multiple – one could argue too high, but there was a compelling reason. The last reason I would give is that, for most of 2015, if you wanted it, you could get a very aggressive debt package on just about any deal.

Richard Herbst (RH): I would say it comes down to expectations vs. reality. There has been a bit of a phenomenon, especially over the last 18 months or so, where the deals that get publicized are the very attractive deals. People tend to shout those from the rooftops. So some companies that are thinking about coming to market are encouraged by these stories, but they don’t really have an appreciation for what the specific auction dynamics were or what the real dynamics were of the company that was able to achieve that multiple. Maybe that company had some outstanding characteristic that was particularly germane to whatever the buyer was interested in, or the buyer had come into a situation where the company wasn’t for sale and the buyer had to offer a real premium because it had tremendous value for them. I also just honestly believe that there is an underreporting of the average and poor deals.

Oscar David (OD): First, I think the growing attention on the mid-market segment has prompted increased competition. Mainly, corporate buyers are paying more attention to this space, and that leads to a rising buyer base. So we see valuations rise for the stronger sellers – those that have strong earnings and strong management teams. We’ve also seen significant improvement of performance among mid-market companies, which have had access to capital and have used that capital to drive their operations – they focus on growth. With greater performance comes higher valuations.

One other factor that may come into play is that the public market has been adjusting its valuations downward of seemingly high-growth companies — meaning those with earnings that aren’t as strong or prospects that aren’t as identifiable. The private market is beginning to catch up in that regard. So you may see the valuation gap start to shrink a bit for the companies that don’t have as strong earnings or prospects.

MM: In which sectors does the valuation gap seem to be most pronounced? Why do you think that is?

AL: I think the biggest gap is in the technology sector. In the tech world, you frequently see companies being sold on unrealized potential – certain buyers are willing to gamble that what they are purchasing is going to be the next Google or the next Uber, which can result in very high sell-side valuations. Certain buyers are willing to take a flyer on tech companies sometimes without having the financials to back it up. Some mid-market tech companies look at the big tech companies that have gone public, or have gotten swallowed up by a company such as Facebook at some extremely high valuation, and think that’s going to work for every technology company out there.

One other thing is that strategic technology buyers are sometimes willing to overpay for a tech company target that just happens to be a perfect fit for their operation. That also raises valuations. PE companies don’t really have that same luxury, but you might see a company such as Cisco, for example, go out and buy some startup at a very high valuation because they feel like that technology will fit perfectly with what they’re trying to do in the future, or will help it to knock out a competitor.

JF: Rather than sectors, I would identify three types of sellers where a valuation gap might be evident. The first is baby-boomer owners. You’ve likely seen reports in recent years that some 10,000 baby boomers are retiring each day, and that trend is going to continue. There is a small percentage of those that represent owners of businesses who are looking to exit, and in my experience this will include individuals who are not experienced with buying and selling companies, and some of them are prone to have valuation expectations that are not going to be realized.

The second type is companies that are going to market because they think the valuations they read about in the papers or hear about from intermediaries might apply to them, and if they’re able to realize that sort of valuation, then they’re prepared to sell the business. So, they go to market, and they have a high sell-price in mind, and those are transactions that are just not closing.

The third type of business that might contribute to this sense of a valuation gap is venture-backed firms in areas where you have a limited number of buyers and the valuations are not based on cash flow. So you might have biotech companies that are developing drugs and tech companies that have unproven business models, maybe even no revenue. But those are companies that at some point are going to sell, and the ambitions they have in the market may be out of whack with what buyers are prepared to pay.

AH: I’ll start out by pointing to sectors where the valuation gap does not appear to be very pronounced. The valuation gap is not as wide for companies engaged in industrial, brick-and-mortar-type industries, and in the energy industry right now, because of all the turbulence due to the low price of oil and gas. The industries where the valuation gap is very pronounced are those that I would refer to as “transformative” industries, involving companies that have substantially higher financial upside. These include companies engaged in the technology, pharmaceutical, and life sciences industries. In the pharmaceutical industry, for example, a company can have one or two breakthrough products that could lead to enormous profitability, and we are certainly seeing significant consolidation in this industry.

The same thing goes for companies focused on technology and life sciences, where, because there is such a great upside, there is a very high valuation gap. Buying into those industries is more speculative; however, with this risk is a corresponding opportunity for very significant returns.

OD: In the telecom space and the life sciences space, I’ve seen significant gaps in what a buyer thinks a business is worth and what a seller believes. We’ve had a lot of discussions over the last 12-18 months about the fact that valuation is a significant factor in these sectors. On the life sciences side, buyers are showing much more scrutiny in terms of where a company is regarding product development and the regulatory approval process. A lot of companies are trying to price themselves as if they already have approval, or as if the product development is going to hit certain milestones. Buyers are simply scrutinizing those factors much more closely.

RH: I think there are two sectors where this is pronounced: high-tech and life sciences. Given certain dynamics, people may bet a lot on the value they think they can create. So, if you look at the life sciences sector, if you believe there is a highly innovative technology and it is particularly applicable to your sales force and your ability to commercialize, they may pay a huge premium. Now, if a related firm sees that company X received this huge valuation, it can set that high expectation, even if their risk profile pushes down what a reasonable valuation expectation could be.

Technology is similar. A high-flying technology company may trade at 5x or 7x revenue if it’s early in its age and is growing very rapidly. But what acquirers are usually paying for is technology that can be monetized and expanded upon. It’s not just unique technology – what they care about is how your technology has been adopted in the market and what sort of momentum you have in the commercialization of it. Competing tech companies like to say, “Well, I have better technology!” But that’s not what acquirers are paying for. Usually, they’re paying because the market has found a certain technology and has been really receptive to it.

MM: What effect do you think a downturn in the US economy could have on valuations of mid-market firms by sellers and buyers? Could a downturn help close the gap?

JF: I certainly think that a downturn could bring down expectations on the sell-side. For owners who are seriously considering a sale, the outlook for lower top-line growth in their business is going to temper their expectations for what a buyer might be prepared to pay. At the same time, it could move some owners to say: “I’m not going to put my company up for sale – I’ll be patient and wait to find another day.” On the buy-side, I think a downturn in the economy might also tighten expectations for what a company is worth, and that might result in more deals getting done because the two sides are going to be more aligned on what the near-term growth of the business will look like.

RH: A downturn may help close the gap, or it may just take companies out of the market. In all fairness, the stock market is not the US economy, and I think the US economy is much more stable than the current market conditions would suggest. But I do think that when the stock market drops like it has, consumer confidence is eroded, and that does have implications for businesses in which people rely on discretionary expenditures. I think people are tightening their belts a little bit.

On the other hand, if there is a significant downturn, potential sellers often say: “I’m just going to wait until my business gets back to where it was.” So you could have people withdraw from the market, because they think they’re only three months, six months, a year or two years away from getting back to where they were and can get those valuations again. It’s an interesting seesaw of expectations.

OD: I’ve talked about this with a number of senior executives on the corporate side and with PE fund partners, and they remain relatively confident regarding valuations, even in light of the economic uncertainty. I’m also not convinced that there will be a significant downturn. But if a downturn does come, do not expect to see a direct correlation with company valuations, on either the private or public side. On the private side, if an owner or seller does not need to sell, the seller will wait it out. On the public company side, a market downturn can impact initial bid prices – I think buyers may come in with lower prices. However, I don’t think this by itself will necessarily impact final pricing.

There will be some kind of market check before a sale is done, whether it’s a full or a partial auction prior to a definitive agreement or a post-execution opportunity to look at superior offers. Ultimately, it’s not just about the downturn itself, but about how the downturn affects the prospects of a particular business.

DA: I think a downturn might close the gap a little bit, as well as dampen the number of deals. I would keep in mind that it’s not one big monolithic M&A marketplace. There are small deals, middle-market deals, and large deals, and I would argue the middle- market deals – by that I mean up to US$100m in enterprise value –benefited most from unitranche lenders because companies and traditional banks aggressively leveraged these transactions. So, we now face a tightening credit market and these same lenders are doing mid-market deals that don’t require syndication, as such. Middle-market deals may be less impacted by tightening credit than larger syndicated transactions.

AH: That really depends on whether a downturn in the economy decreases the availability of credit. Many acquisitions are dependent upon the availability of debt financing, and valuations are often driven by the availability of credit at reasonable terms and rates. In the past two months of so, we have seen a decrease in the availability of credit, and my sense is that this decrease will lessen the valuation gap we saw for most of 2015, because sellers just won’t have the same level of interest they previously had when credit was easier to obtain.

A major competing factor, though, is the need of private equity firms to deploy their capital. Many of these PE firms have substantial assets under management, they’ve raised new funds recently, and there is a need to deploy that capital within a defined investment period. I would also say that as long as there are strategic buyers willing to grow through acquisitions rather than organically, I think there’s a fair chance that valuations will remain extremely high and that the valuation gap we’ve been seeing in the market will continue.

MM: Even with the expanding valuation gap, many deals have been getting done thanks to the availability of cheap financing. But with US interest rates expected to rise, what do you expect to happen to the financing of deals that have a significant gap? Could the higher cost of borrowing help to bring valuations closer together?

RH: Interest rates are still at historically attractive levels right now, so the honest answer is no. There may be a slightly increased urgency on the part of buyers for fear of interest rate hikes down the line, but I don’t think there is the same urgency from the Fed to continue to raise rates after the market correction of the last three to six months. Now, if there start to be signs that the Fed is going to reengage on a series of hikes, I think that will start to temper buyers, and sellers will start to feel that. But right now, if anything, I think there is a sense of urgency among buyers to try to take advantage of the rates that are in place right now. People are still able to get very attractive leverage. Most of the companies we deal with, mostly private equity, are looking at two-and-a-half- to three- times senior debt leverage, up to five-times total leverage on a deal.

OD: Interest rates on bank loans are still historically low. Even if there is an increase, it’s unlikely to be significant enough to raise corporate borrowing costs dramatically. So at this stage, I do not see the possibility of rate increases having a significant impact on M&A in a negative way.

However, on the high-yield side, rates are absolutely having an impact. High-yield rates have increased significantly, because buyers of high-yield paper are demanding higher interest rates and more stringent terms due to global uncertainty. If a buyer is relying on high-yield financing, that will continue to have an impact.

DA: I think in the middle market, you’re going to continue to see good deals getting done. They will probably be at slightly lower valuations, but they’re not going to be as impacted as some of these large deals that go through the banks or the bond houses, where they’re looking at things much more tightly, and they’re syndicating them, so they have to clear the market. In those bigger deals, you’re seeing tightening of credit, increasing spreads, increasing flex language – that’s all there given the market volatility in January.

I also think you have to talk more about the credit spread, because we’re talking about a base rate of LIBOR that’s almost less than 1%. So, a little bit of increase in the Fed funds rate is not going to impact anything. Until you see a material decrease in the leverage that’s available – and I think we’ve seen some moderation of that – I don’t think interest rates are going to have any big impact. If I model a deal at LIBOR +275 versus LIBOR +325 and keep the same leverage, it really doesn’t impact the IRRs. But if I take leverage from five to four, that really impacts the IRRs. You have to look at it as a totality.

AL: If we go through a series of very small rate increases over a long period of time, I don’t think it will have any kind of material effect on the valuation gap. But if people start to feel like cheap credit is drying up, then I could see buyers and sellers getting together and saying, “You know, we better do this deal now, while we can still get cheap debt to do the deal.” The flipside on low interest rates, is it can lead to a shortage of safe investment opportunities that can provide a decent return. In considering a potential sale transaction, I have heard certain business owners question whether an investment in their own business may be their best investment option in current market conditions. They say “I might as well keep running my business for the time being, keep collecting a salary and continue to take appropriate distributions from the business, because my business is generating better returns than current alternatives where I can put the sale proceeds to work.” They wouldn’t make much, if anything, with a “safe” investment at current interest rates, and they may be afraid to put their money in this volatile stock market now as well.

JF: I think the performance of the economy is more important for middle-market valuations than modest changes the Fed might make to interest rates. Fundamentally, the Fed’s actual moves and anticipated moves are something that larger companies are going to spend more time thinking about, since they have a much more complex cap table and more diverse participation in equity and debt markets. For middle-market companies, the movement up and down of interest rates is just not a significant factor for their view on valuations.

MM: How has private equity been affected by the widening valuation gap?

AH:My sense is that the relatively lower level of deal activity is going to continue in the private equity world. I expect that PE sponsors are going to continue to be extremely circumspect about the companies they acquire – notwithstanding our ability as lawyers to deal with uncertainties and to deal with valuation gaps to some extent. In the past, I’ve seen private equity buyers come to terms with companies that had some identified business and financial issues and risks, and we’ve been able to work around the issues through creativity in structuring the acquisition and investment transactions. But when buyers are paying in excess of, let’s say, 12x EBITDA, they’re often simply unwilling to even try to structure around those issues and risks. In 2015, I saw several well-known private equity firms complete far fewer deals than they normally do, and that’s not because they have a lack of capital – it’s simply that private equity money is very “smart” money, and high-quality private equity sponsors remain very disciplined in their approach to potential acquisitions; they are simply unwilling to pursue transactions where they feel they are unlikely to justify these extraordinary high valuations.

JF: There are a few different ways in which private equity firms may be adjusting their game plan or modifying their emphasis. There may be some willingness to pay one turn more for a given transaction, but not, say, four turns more. They understand where their value potential lies in terms of developing a portfolio company, whether it’s based on operating growth and acquisitions, or maybe the use of leverage where it hasn’t been used before, and those approaches just haven’t fundamentally changed.

Second, I’ve seen firms that shift their focus somewhat to look for add-on acquisitions for existing portfolio companies. Those are potential opportunities where operating synergies – such as a reduction in operating expenses, an entrance into new markets, or the leveraging of new products – create value opportunities that allow them to close a valuation gap.

DA: I think the perception of a valuation gap is partly coming from private equity funds who chose to sit on their hands in 2015 because of the high valuations being paid. At the same time, if they were in the market with one of their companies, they wanted those high valuations. But you can’t have it both ways. When you look at the data on how many of the companies sold in 2015 were private-equity-owned, it’s a pretty big percentage. A private equity partner told me that they sold everything in 2015 that they originally planned on exiting in late 2016 or early 2017 because the market was so strong. I think this dynamic will result in fewer companies sold by private equity firms in 2016.

OD: I may go against the grain here, but I think the impact of the valuation gap has been relatively the same on PE firm buyers and on corporate buyers. Both are making investments on behalf of others – in the case of PE, they’re making investments on behalf of their investors, and corporate buyers are making investments on behalf of their stockholders. I straddle both worlds and in my experience, both take their responsibility with extreme care and both groups have an incentive to pursue transactions. I’ve seen some suggest that corporate buyers are more willing to overpay than PE and that’s why PE sat on the sidelines in 2015, but I don’t agree with that. You’re dealing with sophisticated parties on both sides, and I think what’s going on is that both sides are playing to their competitive advantages. The corporate side can often justify a higher valuation, but not because they’re willing to overpay – it’s that they may have synergistic opportunities that a PE fund won’t see. On the PE side, they have the unique feature of providing rollover equity and other financial packages to the management team.

AL: If you look at 2014 and 2015, there were high levels of activity in middle-market PE deals in terms of the number of deals. But one difference we saw between 2014 and 2015 is that the total value of PE deals dropped. As for the effect of the valuation gap on PE, I think PE is getting squeezed more than ever by their investors to get higher returns and, clearly, high valuations become a large impediment to achieving these returns. It’s difficult for PE to compete for top-quality assets in an auction, with the strategics that might be willing to pay top dollar or even over pay in certain instances due to synergies with their existing business. The PE firms will many times determine to pull out of those auctions for the most part, because they’re simply not in a position to match the top valuations and still be able to achieve the desired returns for their investors.

RH: I don’t sense any lack of urgency on the part of private equity buyers to go buy the good deals. I think what they’re finding is that it’s tougher and tougher to find that good deal. Especially when it comes to the more value-oriented funds, they have specific limitations on these super-high multiples. They’re limited to a specific range, and if they can’t find deals in that range, there’s no deal to be done.

MM: In your M&A experience, what are some ways that sellers and buyers have closed the valuation gap to get a deal done?

AH: There are three primary ways that sellers and buyers are able to effectively close the valuation gap and get a deal done. The first way is to structure a portion of the purchase price as an earn-out, so that the payment of part of the deal consideration is dependent upon the achievement by the target company of the financial and business results that they have forecasted and that have formed the basis for the underlying valuation. The second way that private equity sponsors have been able to address these valuation gaps is by requiring an even higher proportion of management equity rollover. So, where in the past we might have seen 15%-25% of the total equity rolled over by existing management in the transaction, one way to share that risk and to try to close the valuation gap is by requiring management to roll over substantially more of their equity – for example, from 25% to as much as 45% of their equity in the target company. The third way that private equity buyers have been able to come to terms with these high valuations is by bringing in co-investors. Instead of taking the entire deal, we are seeing some private equity sponsors taking a lesser portion of the entire transaction and bring in co-investors, either from their existing limited partnership base or from outside their fund.

RH: One thing that a buyer can do is speak to things that are important to a seller beyond just the pure price of the company. A lot of the people who sell middle-market companies have a real sense of stewardship – they’re often in a company town or are a significant employer in the community. And if buyers express their willingness to create opportunities for employees and to foster the community, you can differentiate yourself. Those factors can get you beyond a pure price discussion.

Beyond that, there are really two things that people use to bridge the gap. One is the ability for people to participate in rollover equity, allowing the seller to participate in the value a buyer is going to put into the investment. The second one is an earnout, where there’s just a difference in expectations as to what the future can look like.

AL: One way that parties try to close the gap is for buyers to agree to more seller-friendly terms in their contracts. So, for example, they may be willing to agree to a slightly higher basket, or maybe a slightly lower cap on indemnity, to entice risk-averse sellers to take a lower price. Some buyers may be willing to agree to a deal without any or a lower indemnity escrow, so that sellers can put more money in their pockets up-front. Another thing is rep-and- warranty insurance, which buyers will sometimes buy to alleviate some post-close risk for sellers. And then the most obvious deal mechanic to handle a valuation gap is earnouts, which are good to help bridge these kinds of gaps, but at the same time can be a hotbed for disputes later on.

OD: Earnouts are an important tool, but they come with risk. There’s a famous quote by Delaware Vice Chancellor Travis Laster that makes a really important point: “An earnout provision often converts today’s disagreement over price into tomorrow’s litigation over the outcome.” I advise clients to keep that in mind when it comes to earnouts. That being said, we do them all the time, and the details, mechanics, and contractual protections of them are scrutinized with great caution and care.

DA: We’ve seen buyers, primarily PE, be very creative. For instance, we’ve seen certain PE firms offer to put the subordinate or mezzanine debt in themselves, then share some of that with the seller – meaning the seller actually helps finance the acquisition by taking some of the paper, and gets a good interest rate on it. We have not seen earnouts back yet, and I don’t foresee us starting to do them, but obviously that’s another way that you can bridge the gap.

JF: One way that I’ve seen the gap bridged is through a contingent payment. When a valuation gap is based on specific exposures, we’re also seeing more deals done that have a general escrow and then a situation-specific escrow. So it could be, for example, a disputed tax liability, or a pending lawsuit, or some other exposure that the two parties could disagree on. In some of those cases, the valuation gap can be closed by agreeing on how the ultimate disposition of that liability is going to be handled, separate from the core business.